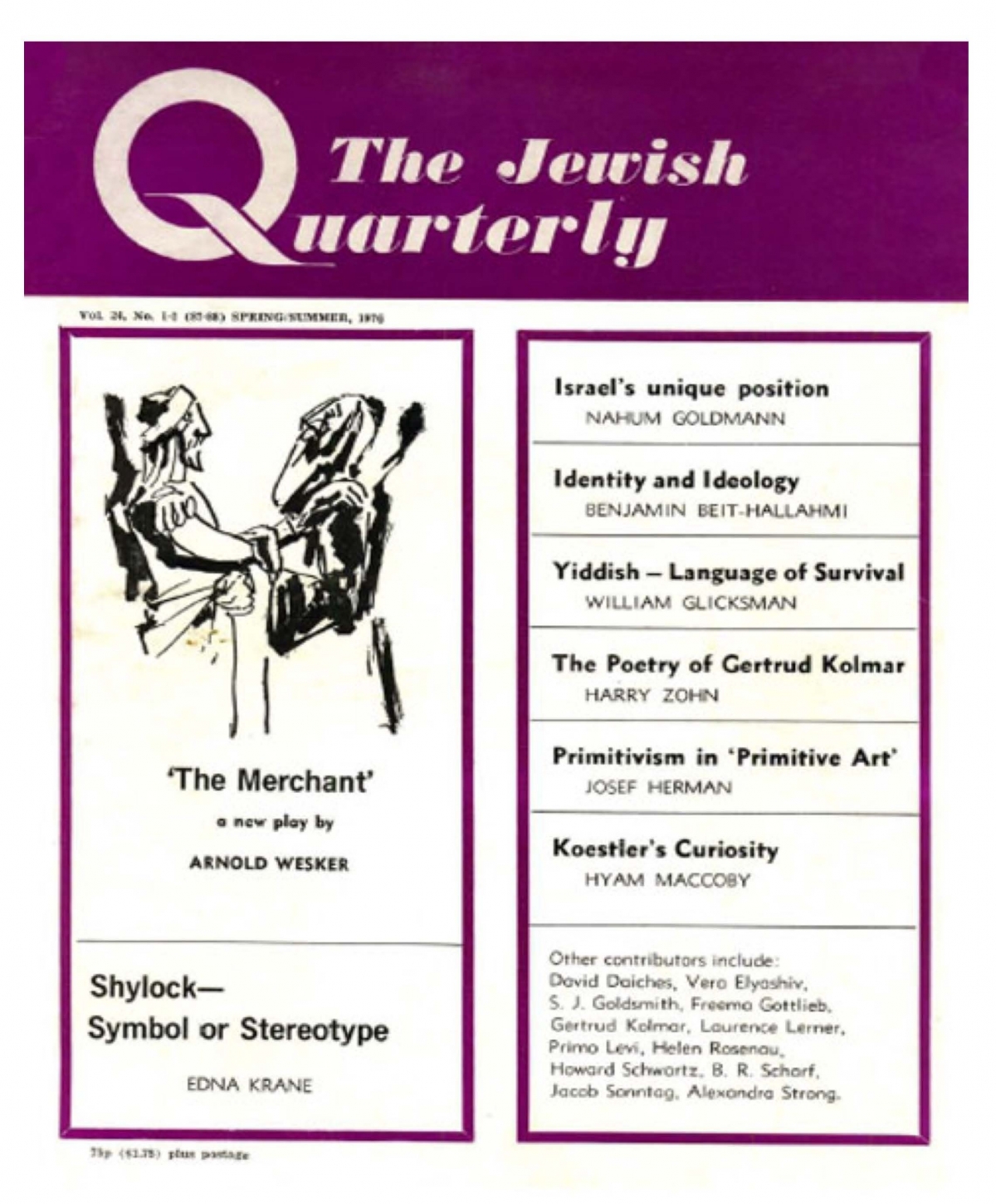

Although based on most of the characters in Shakespeare’s play and ostensibly using the same story, The Merchant develops Wesker’s interpretation to a dialogue between Judaism and Christianity on the supremacy of the Jewish attitude to law and justice.

ACT ONE

SCENE ONE

Venice, 1563. The Ghetto Nuovo. Shylock’s study. It is strewn with books and manuscripts. Shylock, a ‘loan-banker’, with his friend, Antonio, a merchant, are leisurely cataloguing. Antonio is by the table, writing, as Sherlock reads out the titles and places them on his shelves. They are old friends and old; in their middle sixties.

SHYLOCK: (reading out) ‘Lesser book of precepts.’ Author, Isaac of Corbeil. England. Thirteenth century. (Antonio writes) Hebrew/English Dictionary. Author, R. David Kimhi. England. Thirteenth century. Not too fast for you, Antonio?

ANTONIO: It's not the most elegant script, but I'm speedy.

SHYLOCK: And I'm eager. I know it. But here, the last of the manuscripts and then we begin with the printed books. Such treasures to show you, you'll be thrilled, thrrrrrilled! You'll be – I can’t wait. But write, just one more . . .

ANTONIO: Do I complain?

SHYLOCK: … and then we'll rest. I promise you. I'll bring out my wines, and fuss and – the last one. I promise, promise.

ANTONIO: Shylock! Look! I'm waiting.

SHYLOCK: I have a saint for a friend.

ANTONIO: And what does the poor saint have?

SHYLOCK: An overgrown schoolboy. I know it! The worst of the deal. But . . .

ANTONIO: I'm waiting, Shylock.

SHYLOCK: Deed. Legal. Anglo-Jewish. Twelfth century. Author – I can't read the name. Probably drawn up by a businessman himself. (peering) What a mastery of Talmudic Law. I love them, those old men, their cleverness, their deeds, their wide-ranging talents. Feel it!

ANTONIO: The past.

SHYLOCK: Exactly!

ANTONIO: And all past.

SHYLOCK: Antonio! You look sad.

ANTONIO: Sad?

SHYLOCK: I've overworked you. Here. Drink. Why should we wait till we're finished? (offers wine) Drink. It's a special day.

They drink in silence.

ANTONIO: So many books.

SHYLOCK: And all hidden for ten years. Do you know what that means for a collector? Ten years? Ha! The scheme of things! “The Talmud and kindred Hebrew literature? ‘Blasphemy!’ they said, ‘burn them!’" And there they burned, on the Campo dei Fiori in Rome, decreed by Julius Third of blessed origin, and followed swiftly by our very own and honoured Council of Ten in Venice. August 12, 1553 – the day of the burning of the books. Except mine. Which I hid. Everything. Even my secular works. When fever strikes them you can't trust those warriors of God. With anything of learning? Never! That's what they really hated, not the books of the Jews but the books of men. I mean – MEN. Their spites, you see, it revealed to them their thin minds. And do you think it’s over even now? Look! (pushes out a secret section of his bookcase.) The Sacred Books. The others I can bring back, but still, to this day, the Talmud is forbidden. And I have them. The greatest of them. Bomberg's edition. Each of them. Starting 1519 to the last on June 3, 1523.

ANTONIO: So beautiful.

SHYLOCK: (referring to others) Some I'd forgotten I had. Some I didn't even have a chance to look at, they'd just arrived. From here, from there. I've friends who buy for me all over the world. They kept coming. So—drink! It's a special day. I'm a hoarder of other men’s genius. My vice, my passion. Nothing I treasure more, except my daughter.

Antonio, looking at this and that reads from something pasted to the side of the bookcase.

ANTONIO: ‘July 12, 1555. Forasmuch as it is highly absurd…’ What is it?

SHYLOCK: Read it, read it. A papal Bull. Another mad edict. I kept it. I'm a hoarder, of other men’s genius, remember? ‘Cum Nimis absurdum’, forasmuch as it is highly absurd . . .

ANTONIO: ‘Forasmuch as it is highly absurd and improper that the Jews, condemned by God to eternal slavery because of their guilt, should, on the pretext that they are cherished by Christian love and permitted to dwell in our midst, show such ingratitude to Christians as to insult them for their mercy and presume mastery instead of the subjection that beseems them; and forasmuch as we have been informed that in Rome and elsewhere their shamelessness is such that they presume to dwell among Christians in the neighbourhood of churches without distinction of dress, and even to rent houses in the more elegant streets and squares of the cities, villages and places in which they live . . .’ Oh! I can’t go on.

SHYLOCK: Such pompous language the malicious use to proclaim their righteousness. Was that a nice Bull, I ask you? (Listing) No work on Christian holidays, no association with Christians on familiar terms, no title of respect, no Jewish physicians to attend Christian patients, only one synagogue per city, yellow hats to be worn again – and on the Piazza San Marco more books burned. Was that a Pope? Cardinal Carraffa! He's fortunate it is my God in charge or he'd be in hell by now. Oh, forgive me. An arrogant joke. First I tire you then I depress you, then I insult you.

ANTONIO: I'm not tired, Shylock, except to go looking for insults where intelligence is.

SHYLOCK: Look! A present. To cheer you up. One of my most treasured manuscripts, a Talmud of the 14th century, with additamenta made by the students. I used to do it myself – study the Talmud and scribble my thought in the margin. We all did it. We had keen minds, Antonio, very profound we thought ourselves, commenting on the meaning of life, the right and wrongs of the laws, offering our interpretations of the interpretations of the great scholars who interpreted the ‘meaning of the meaning of the prophets.’ Did the prophecies of Daniel refer to the historic events or to Messianic times, or neither? Is the soul immortal, or not? Should one or should one not ride in a gondola on the Sabbath?’ And do you think I still don’t dispute – the infidels with the pious; Ha! I love it! The Ghetto rocks with argument. Money-lending is hardly a full-time occupation, and time hangs heavily. There! I have tired you.

ANTONTO: I assure you . . .

SHYLOCK: Depressed you, then. I've done that.

ANTONIO: Not that either. But...

SHYLOCK: But what? What but, then?

ANTONIO: Those books. Look at them. How they remind me what I am, what I've done. Nothing! A merchant! A purchaser of this to sell there. A buyer up and seller off. And do you know, I rarely even see my trade. I have an office, a room of ledgers and a table, and behind it I sit and wait till someone comes in to ask have I wool from Spain, cloth from England, cotton from Syria, wine from Crete, And I say yes, I've a ship due in a week, or a month, and I make a note, and someone goes to the dock, collects the corn, delivers it to an address, and I see nothing. I travel neither to England to check cloth, nor Syria to check cotton. I haven't even the appetite to visit the lovely island of Sante to inspect the raisins, or Corfu to see that the olive oil is cleanly corked. And I could holiday in such places if I wished. It worried me, once, this absence of curiosity for travel. Until I met you, old Jew…

SHYLOCK: Not so old then, old man, only just past fifty…

ANTONIO: … and I became caught up in your, your passion, your hoardings, your, your vices!

SHYLOCK: Is he complaining or thanking me?

ANTONIO: You've poisoned me, old Shylock, with restlessness and discontent, and at so late a time.

SHYLOCK: He's complaining.

ANTONIO: A lawyer, a doctor, a diplomat, a teacher — anything but a merchant. I'm so ashamed. There's no sweetness in my dealings. It's such a joyless thing, a bargain. After the thrill of the first exchange, after the pride of paying a thousand ducats with one hand and taking fifteen hundred with the other — no skill. Just an office and some ledgers. I'm so weary with trade.

*

ACT ONE

SCENE TWO

Belmont. Portia’s estate outside Venice.

The Estate is in great disrepair. Portia and her maid, Nerissa, in simple, hardwearing clothes, just arrived to view the neglect.

PORTIA: Decided! The speculating days of the family Contarini are done. The goods warehoused in our name at Beirut and Famagusta we'll sell off cheaply to cut our losses, I shall raise what I can from the sale of our properties on Crete, Corfu and the Dalmation towns which are too far from Venice and not worth their troubles. But…

NERISSA: …but agriculture, my lady. What does my lady Portia know of agriculture?

PORTIA: Your lady Portia will learn, Nerissa. The famines are cruel and constant visitors. We must reclaim the land, Besides, the competition for the trade routes is too devious a task for my taste, and…

NERISSA: …and pirates are in the Adriatic, we know all that, my lady, most demoralising for our sailors, but…

PORTIA: Antwerp! Seville! London! Too far! I neither enjoy nor can plan for vast tracts of water.

NERISSA: But to leave the city?

PORTIA: I hear rumours, Nerissa, from customs officers. Timber is scarce, the number of ships registered in Venice is dropping. Signs, my dear, the signs are there. I love my city but — it’s goodbye to Venice, and into the wheatlands of my estates near Treviso and Vicenza and here,

Belmont. Growers! Stockbreeders! That's what we'll become. Cattle, implements, irrigation, drainage — that’s where our fortunes will go.

NERISSA: When you've realised them, that is.

PORTIA: The land! I've decided! (pause) Good God! (looking around) What a mess my father's made of my childhood. (pause) Is this the room?

NERISSA: Facing the sun at eleven o'clock. This is it.

PORTIA: And here we are to find the caskets?

NERISSA: Here. Somewhere. Your father’s puzzle for picking a spouse. One gold, one silver, one lead.

Nerissa extracts a stand from a dusty corner.

NERISSA: Found! ‘By his choice shall you know him’.

PORTIA: What a device for fortune! What an inheritance! Ten estates in ruin. It'll take me a decade to put the estates right, and that device will find me an idiot husband as my help. Oh father, father, father] What were you thinking of? Hear me up there. I will honour the one wish you uttered: whom the casket chooses, I’ll marry. But your rules for judging men I will forget, and these ruins will be put back again. The material things of this world count. We have no soul without labour. And labour I will, father, hear me.

She begins to move about the room pulling down tattered curtains, replacing furniture on its feet, picking up strewn books, perhaps rubbing encrusted dirt from a vase till its frieze can be seen, but moving, moving.

NERISSA: How your mother would love to be alive now, with all this possibility of work at last.

PORTIA: Perhaps that’s my real inheritance, Nerissa: father’s marriage to a peasant. My energy is hers.

NERISSA: And such energy, madame.

PORTIA: All stored and waiting for the poor man’s death.

NERISSA: Come, be just. He didn’t commit you in marriage at the age of seven as my father did. He gave you tutors.

PORTIA: Ah, thank heaven for them.

NERISSA: A very strange collection, I used to think.

PORTIA: The crippled Ochino from Padua for mathematics, the boring Lemberti from Genoa for History…

NERISSA: The handsome Mansueti from Florence for Greek and philosophy . . .

PORTIA: And for Hebrew, Abraham Cardorso, the sad, old Jewish mystic from Ghetto Nuovo. I am indebted to them all.

NERISSA: Why did you want to learn the Hebrew tongue, my lady?

PORTIA: To read the words of the prophets in the language they were spoken, why else? Meanings change when men translate them into other tongues. Oh! Those caskets! Those stupid caskets! Take them out of my sight, I loved him dearly, my father, but those caskets will bring me down as his other madnesses brought down my mother, I feel it.

NERISSA: Such energy, madame you tire me to watch you.

PORTIA: And you must have it too, Nerissa, I demand it. I’ll have you educated against the confusions of an ignorant world, and protected from the miseries of an ill-chosen marriage.

NERISSA: If, that is, you can protect yourself from one.

PORTIA: True! My God, how they come. The speed with which the story travels. From all over the world. Some go as soon as they see the condition of things. Others make appointments to choose later, which they know they'll break.

NERISSA: And some go, flee I'd say, as soon as they meet you.

PORTIA: Mercifully! But still they arrive. Why, do you wonder, is there such interest in me?

NERISSA: Riches, madame, riches, riches, riches.

PORTIA: But my riches are potential, not realised.

NERISSA: The family name?

PORTIA: My family name is illustrious but somewhat moth-eaten.

NERISSA: Your beauty.

PORTIA: No flattery. I won't have it. My beauty is, well—it is, but no more than many such women of Venice I could name.

NERISSA: Why, then? You say.

PORTIA: I think I know, but it's not certain. There are simply – mmm – pulses in my veins, I feel, I feel – I feel I – am – the – new – woman – and – they – know – me – not! For centuries the Church has kept me comfortably comforting and cooking and pleasing and patient. And now – Portia is no longer patient. Yes, she can spin, weave, sew, milk, she can turn butter and make cheese. Give her meat and drink – she can dress them. Show her flax and wool – she can make you clothes. But—Portia reads! Plato and Aristotle, Ovid and Catullus, all in the original! Latin, Greek, Hebrew…

NERISSA: With difficulty!

PORTIA: She has read history and politics, she has studied logic and mathematics, astronomy and geography; she has corresponded with philosophers, written commentaries, disagreed with statesmen, and conversed with liberal minds on the nature of the soul, the efficacy of religious freedom, the very existence of God!

NERISSA: Why! Her brain can hardly catch its breath!

PORTIA: She has observed, judged, organised and – lost innocence, for there is knowledge of love and corruption in her, and pleasure and evil. She has crept out of the kitchen and the fireside chair, and what she will do now is a mystery. No one knows. Portia is a new woman, Nerissa. There is a woman on the English throne. Anything can happen and they have come to find out.

*

ACT ONE

SCENE THREE

Shylock’s study. He and Antonio have been drinking.

SHYLOCK: I gave you wine to cheer you up. It's cheered me down!

ANTONIO: The work's done. You should be happy. I've lost the use of my hand, but what of that? Look, order! Filed, catalogued, all that knowledge. You could save the world.

SHLYOCK: When I can't be certain of saving myself? What a thought! Here (reaching for a book) one of my most extraordinary finds: an elegy written on the Martyrs of Blois by the Rabbi Yom Tov of Joingy. What a lovely old man he must have been. To a question once about whether or not to use a stove on the Sabbath, he replied ‘May my lot be with those who are warm, not those who are stringent!’ Poor sage. They were all poor sages. Read much more than I do, and they couldn't save themselves. Constantly invited to run educational establishments here and there, and never certain whether they were running into a massacre. They fled from the massacre of Rouen into the massacre of London, from the massacre of London to the massacre of York – from which no one fled! Poor Rabbi Yom Tov! Died in York having been invited from France to supervise a Talmudic academy – pouf! Out went his light in the year of your Lord 1190. And just one year after the massacre of London where another Rabbi, Jacob of Orleans, a scholar of scholars, probably brought over by a wildly fervent layman to live in his house and direct his studies and those of his family – pouf! Out went his light in the year of your Lord 1189. (pause) Third of September (pause). Travelling wasn’t very safe in those days!

ANTONIO: Are you a religious man, Shylock?

SHYLOCK: What a question. Are you so drunk?

ANTONIO: You are religious, for all your freethinking, you're a devout man. And I love you for it.

SHYLOCK: You are so drunk. Religious! It's the condition of being Jewish. Like pimples with adolescence. Who can help it? Even those of us who don’t believe in God have dark suspicions that he believes in us. Listen, I'll tell you how it all happened. Ha! The scheme of things! I love it! Imagine this tribe of semites in the desert. Pagan, wild, but brilliant. A sceptical race, believing only in themselves. Loving but assertive. Full of quarrels and questions. Who could control them? Leader after leader was thrown up but, in a tribe where every father of his family was a leader, who could hold them in check for long? Until one day a son called Abraham was born, and he grew up knowing his brethren very, very well indeed. ‘I know how to control this arrogant, anarchic herd of heathens,’ he said to himself. And he taught them about one God. Unseen! Of the spirit! That appealed to them, the Hebrews, they had a weakness for concepts of the abstract. An unseen God! Ha! I love it! What an inspiration. But that wasn't all Abraham's real statesmanship, his real stroke of genius was to tell this tribe of exploding minds and vain souls: ‘Behold! An unseen God! God of the Universe! Of all men! and, wait, for here it comes, and of all men you are his chosen ones!’ Irresistible! In an instant they were quiet. Subdued. ‘Oh! Oh! Chosen? Really? Us? Ssh! Not so loud. Dignity! Abraham is speaking. Respect! Listen to him. Order!’ It worked! They had God and Abraham had them. But – they were now cursed. For from that day moved they into a nationhood that had to be better than any other and, poor things, all other nations found them unbearable to live with. (pause) What can I do? I'm chosen. I must be religious.

ANTONIO: I love you more and more, Shylock. You have a sanity in this mad world I could not live without now. I'm spoiled. Chosen also.

SHYLOCK: But sad, still. I can see it. I've failed to raise your spirits one tiny bit.

ANTONIO: I'm not a religious man. I had a letter today, from an old friend, Ansaldo Visconti of Milan, a rich merchant, and well-loved in my youth. But I'd forgotten him. And in this letter he talked of his misfortune, his downfall into ruin through strange and cursed events which I couldn't make any sense of, it was so wordy and maudlin and full of old times. And in the end he commends me to his only son, Bassanio, my Godson it seems. And I'd forgotten him also. Poor young Bassanio, Probably a very noble young nobleman. I even think he must be a young patrician. His father was born in Venice, if I remember, of patrician stock, if I remember. No, he’s probably a swaggering young braggart! Coming to see me in the hope I'll put trade his way, or put him in trade's way, or keep him by me as an assistant, passing on wisdom, or something. (pause) Here, Bassanio, a little piece of wisdom, here, in my pocket. (pause, mock pomp) I am now going to be wise! (pause. Then as if calling a dog). Here, wisdom, here boy. Sit. Still. Quiet now. There, Bassanio, sits wisdom. (pause) I don’t want to be wise, or to talk about trade, or to see him. Ungodly man! Doesn’t that make me an ungodly man? I should never have had Godsons. Not the type. Bachelor merchant. On the other hand I suppose that’s just the type,

SHYLOCK: When do you expect him?

ANTONIO: Oh, tomorrow, or the next day, or is it next week? Can't remember which. Bassanio! Humph! (shouting out) I'm not a religious man, Bassanio.

SHYLOCK: Antonio, my friend, it's late. In ten minutes they lock the gates of the Ghetto and all good Christians should be outside.

ANTONIO: I may be your Godfather, Bassanio, but I'm not a religious man.

SHYLOCK: I have a suggestion.

ANTONIO: Bassanio, Bassanio!

SHYLOCK: Stay the night.

ANTONIO: Stay the night?

SHYLOCK: It’s not permitted, but with money…

ANTONIO: What about Bassanio, in search of wisdom?

SHYLOCK: We'll send a message in the morning to say where you can be found. Stay. You know my house, lively, full of people in and out all the time, My daughter. Jessica, will look after you— if she deigns to talk that is.

ANTONIO: Very haughty, your Jessica.

SHYLOCK: And free and fractious but —cleverer than her illiterate old father. Gave her all the tutors I couldn’t have. But I've got one now.

ANTONIO: (Trumpeting) Abtalion da Modena the illustrious!

SHYLOCK: My very own scholar.

ANTONIO: (Still trumpeting) On his very own pilgrimage from Lisbon to the holy Jerusalem, financed by his very own pupil here, Shylock Kolner, in return for his very own wisdom. (As if calling a dog) Here, wisdom, here, boy!

SHYLOCK: Stay! You enjoy him. And you know how the Ghetto is constantly filled with visitors. Always some visiting foreign Duke, or Ambassador coming to see the sights of the Jewish quarter, to listen to the music, attend the festivals. Stay. In the morning Solomon Usque the writer is coming with the daughter from the Portuguese banking house of Mendes, and in the afternoon we'll go to the synagogue to hear the sermon of a very famous Rabbi from Florence. Preaching on the importance of the Talmudic laws on cleanliness. With special reference to Aristotle! Stay. It'll be full of Venetian intelligenzia. Very exotic we are. We fascinate them all, whether from England where they've expelled us, or Spain where they burn us. Stay. (pause) He's asleep. He'll have to stay.

Taking an arm of the now half-asleep Antonio, he struggles with him towards a bedroom.

And if the gatekeepers remember and come looking, don’t worry, I'll keep them happy. Happy, happy, happy.