What was the role of Jews in the Hungarian Revolution of 1956? That can be answered in three words: waiting, seeing, leaving. That, at any rate, is how it was with us and with some 20,000 others, which left about 80,000. Why did 20,000 leave?

Why do Jews leave any place? The usual reasons. It’s just that the usual reasons are always complicated, as in this case. The complications are historical. The Hungarian story, which may be traced back to the tenth century, is the familiar one of Jews either seeking refuge or being invited in to help the economy along. They take up positions of responsibility and are then resented by the rest of society. They are persecuted and expelled but when they are needed again or expelled from elsewhere, they return. Often, they are required to live in ghettos or to wear some identifiable mark of their Jewishness. These readmissions and expulsions follow hot on each other's heels. Too ss, particularly conspicuous success, brings on a pogrom. When they, and the country, do well, they are suspected of enriching each other at the expense of the rest; in poor times, they are an alien, troublesome underclass. The underlying perennial question asked by the majority is that of identity. Is a Jew a citizen or a Jew? If both, in whose interests are Jews acting? Whom do Jews put first?

It may be said that the modern era for Hungarian Jews began after the uniting of the Austrian and Hungarian monarchies in 1867. This followed the revolution of 1848 where many Jews fought with distinction on the nationalist side against the Austrians and the Russians. The reward for this was a brief two-week emancipation on the condition that they reformed their religious practices. However, then the Russians defeated the revolutionary forces and it was back to persecution. In 1867, Jews were at last emancipated and entered fully—and very successfully—into civic life. The period from 1867 to 1919 was a golden period for Hungarian Jewry. Budapest was the fastest growing city in the world, and almost a quarter of the population was Jewish. The schism between Orthodox and Neolog Jews in 1869 led to greater assimilation of the Neologs. Neolog Jews were spread through the various classes and many rose to prominent places in industry, finance, medicine, the press and culture. They were also to be found at the other ideological end of society, as radical thinkers. Their rise was followed by the customary resentment from the rest of the country and from the empire at large. Budapest was simply “Judapest” to some; a city of decadence, corruption and depravity, hated by both the old landed aristocracy and the conservative church. The provinces both envied and recoiled from the sinful metropolis. The Great War put an end to that. It was the greatest trauma suffered by the country since the Ottoman invasion of 1526. It took a vast military toll. Hungary suffered the largest ratio of loss among the Central Powers; workers went on strike, soldiers rebelled and the economy collapsed. Two revolutions followed. The first was the Aster Revolution of 31 October 1918 that declared the Republic of Hungary with Count Karolyi at its head. The second was the Bolshevik Revolution of March 1919, led by Béla Kun. This was the crisis point for Hungarian Jews. Kun was Jewish, as were a number of his closest associates, such as the philosopher Gyorgy Lukacs and the future Stalinist dictator Matyas Rakosi.

By the time Kun came to power, Hungary was practically defenceless. With help from his own fighting force, the Lenin Boys and the Red Army, Kun promised to protect Hungary against the insurgent subject states of the empire, who were moving into pre-war Hungary on various fronts.

He announced the dictatorship of the proletariat, set up workers’ councils, nationalised industries, expropriated property and operated what became known as a “red terror” against the opposition. But then, to the astonishment of the Hungarians, the Romanian army swept into Budapest, the dictatorship of the proletariat collapsed and Kun was forced to flee to Russia where he was later executed in a purge in 1930. Kun’s fall was quickly followed by a right-wing reaction led by Admiral Horthy. Horthy initiated a “white terror”, mostly against communists but also against Jews, since Jews at large were regarded as Bolsheviks. And not only Bolsheviks, of course, but also as the wickedest of financiers and industrialists. They were on both sides at once, and all the more culpable for that. One story of the period suggests that the Jewish-born writer Tibor Déry was a member of the committee that expropriated his own wealthy father. After the war, under the terms of the treaties of Versailles and Trianon, almost three quarters of Hungarian territory was transferred to neighbouring states and the country lost some two thirds of its population (although only a third of the lost population was ethnically Hungarian). This trauma is still the greatest popular cause in Hungary and any politician can call upon it to summon not only patriotic, but also intense nationalist feeling. Jews constituted almost half of the Hungarians who found themselves in alien territory. My own mother was an ethnic Hungarian, born in what had just become Romania. Drawing attention to oneself as a Jew was becoming ever more problematic. The first anti-Jewish laws were drawn up in Hungary in 1920. Jews changed their names, hid their identity and tried to remain as inconspicuous as possible. Life was still tolerable but was being squeezed. I need not describe the Holocaust here. Its general outlines are too well known and there is not much room or need for further detail. The Second World War meant years of increasing hardship, but the deportations and death camps only got fully under way in March 1944 when the Germans deposed Horthy, took control, put Eichmann in charge and established the fascist militarised Arrow Cross as the government. The Jews of pre-Trianon Hungary were the first to be deported, followed by those of the provinces and then of Budapest itself, though by that time the Red Army was already crossing the frontier. That did not diminish the efforts of the Arrow Cross to exterminate the Jews. They were fanatical in their mission. Nevertheless, about 120,000 Jews survived in Budapest. The estimated survival rate in Hungary was roughly 30%.

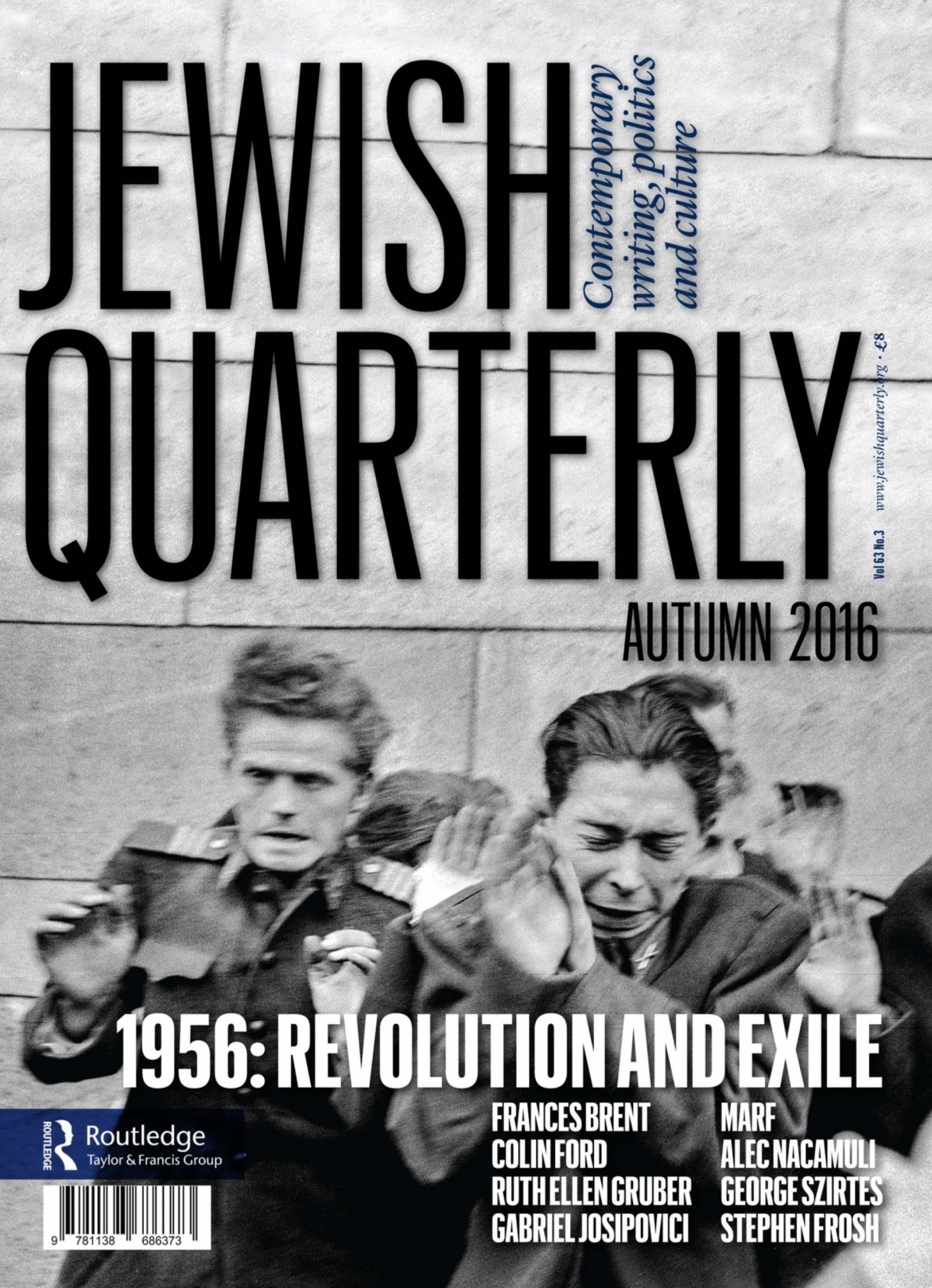

There was terrible chaos after liberation. People emerged starving from cellars. Stagflation ensued on a world-record scale. The Russian occupation ensured that within four years the communists had established themselves in exclusive power. The head of the new regime was Matyas Rakosi, who had fled to Moscow in 1919, returned to Hungary in 1924, was imprisoned and then released to exile back in Moscow, in 1940. Rakosi and his chief lieutenants—his deputy Ern Gerd, the head of the security police, Gabor Péter, and the culture minister Jozsef Révai—were all Moscow-trained, all Jewish by birth, all secularised, all with changed names. The Bolsheviks were back, not as the Lenin Boys, but as the Stalin Boys. In 1949, Rakosi arranged a show trial of his then minister of the interior, the non-Jewish, non-Moscow-trained, Laszlo Rajk, and had him tortured and executed. In a country long prone to antisemitism this, though only whispered (it was far too dangerous to talk), was certainly noted. Ironically enough, antisemitism continued to operate at lower levels, nor was there any philosemitism at the top, but the Right, even now, have never forgotten that Matyas Rakosi was born Rosenfeld. Following the death of Stalin in 1953, Rakosi lost his position and was replaced by a more liberal figure, Imre Nagy, who lasted only a year before being dismissed for rightist deviation. It was the return of Rakosi, together with the beginning of the de-Stalinisation process in the wake of Khrushchev’s secret speech to the Twentieth Congress of the Communist Party and the subsequent strikes in Poland, which sparked the 1956 revolution in Hungary. Rajk was reburied with full honours at the beginning of October and on 23 October, following demonstrations and shootings at the radio station, the country went up in flames.

Was there a specific Jewish role in this? Jews did participate, of course, though not as Jews. Tibor Déry became a spokesman for the revolution, as did Gyorgy Lukacs. They wrote, agitated and advised. Lukacs became a minister in Nagy’s government.

My mother insisted my father stay at home but he went out and about to observe what was happening. There was fighting on our street. A bullet flew in through the window, ricocheted off the ceiling and hit the toy watch I was wearing at the time.

After the defeat of the thirteen-day revolution, Déry, who was 62 at the time and recognised by many as one of Hungary's most important living writers, was sentenced to nine years in prison, and served four. Lukacs who, as a leading party member under Rékosi had, through his criticism, been responsible for the silencing and imprisonment of writers and philosophers who did not conform, was deported to Romania, like Nagy. Unlike Nagy, who was secretly hanged in 1958, Lukacs survived.

Perhaps the best-known Jewish figure of the 1956 revolution was Istvan Angyal. Angyal, who was just 30 when the revolution broke out, was born to a Jewish family in the provinces and had survived Auschwitz. He returned as a communist but did not join the party, possibly because his bourgeois background might have prevented him, as it did my mother. He started university on his return but was expelled for supporting Lukacs in 1949 when Lukacs was under ideological attack. He worked in a steelworks, received a Stakhanovite medal for record production but, being an idealist, grew disillusioned with socialism as it existed. He became part of the Budapest intellectual circles critical of Stalinism in 1956 and joined the demonstration at the state radio station on 23 October. He fought in the revolution, composed revolutionary verses and texts, and became the leader of one of the many small military groups. At the end of the revolution, he was arrested, put on trial and hanged. A park in Budapest is currently named after him. Angyal is certainly recognised as one of the more heroic figures of 1956 but he did not fight as a Jew, nor was he arrested and executed as one. It would be hard to embody the Jewish role in 1956 in Angyal. In the case of my own family, my mother had survived two concentration camps and my father a series of labour camps. Both were secular atheists, though my father retained some cultural sense of Jewishness. My mother, who had lost all of her own family, wanted nothing to do with it. Religion, as religion, meant nothing to either of them.

In the course of the revolution—only some eleven years after the war—prisons were opened and some of those involved in the persecution and murder of Jews were set free. There were cries of “finish the job!” —meaning the job of extermination. My parents heard them.

Antisemitic incidents do not characterise the revolution as a whole. Such cries were rare and the revolution was as honourable as a revolution can be. People left money in the streets for the wounded. People acted kindly and heroically. No one, as far as I am aware, asked my parents whether they were Jewish. Nevertheless, even a small outburst of patriotic, ultra-nationalist feeling, combined with the opportunity to leave, meant my mother leapt at the chance. She feared for my father and her children. He, in turn, though less keen to leave, agreed that Hungary had a tendency towards antisemitism. He too had experienced it. I asked him later why we left. Was it because of any part he had played in the revolution? “No,” he said. “If you are looking for heroes, I am not one. We left at your mother’s insistence.” Many Jews must have felt the same because they made the same decision. Following the war, my father changed the family name of Schwartz to the more Hungarian Szirtes. This is something else I discovered later than I might have. In Budapest in 1991, a friend asked me what my real name was. I told him and then he told me his. I had no idea he was Jewish.